There's a Secret to a Nearly Painless IUD. Republicans Can't Stand It.

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

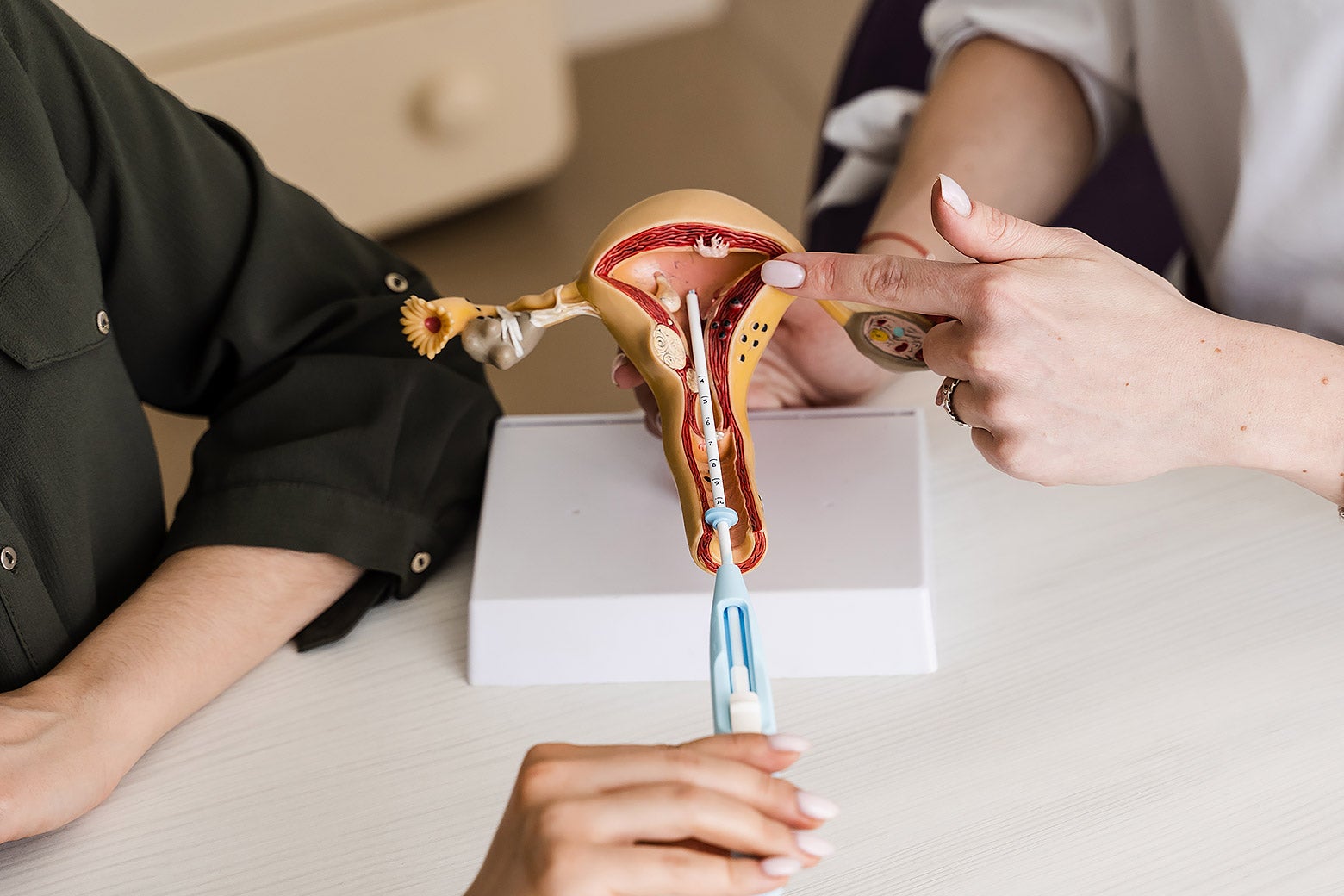

When the lidocaine was injected into her cervix, Leah Wells said it felt like fuzzy lightning traveling up her body. In addition to numbing her cervix, the medication made her mouth tingle, and she felt a little stoned. It was during that brief high that Wells' gynecologist inserted an intrauterine device, or IUD.

In terms of contraception, an IUD is arguably second to none, as it is more than 99 percent effective. But getting one can come with a cost. While some patients report only mild cramping from an insertion, others describe a stabbing or searing pain that rivals childbirth.

These real-life tales of body horror had scared Wells off an IUD until this January, when President Donald Trump returned to the White House. The growing threat to contraception and abortion access changed her mind, as an unplanned pregnancy can be its own type of terror.

“I wanted to protect my choice not to be pregnant,” Wells told me.

It turned out that getting an IUD wasn't a big deal for Wells because the lidocaine did its job. She recalls that her pain reached what she would end a 3 out of 10, for a total of maybe 15 seconds. This is Wells' first IUD, so she can't compare a medicated insertion to an unmedicated one. However, Wells' experience might have been far more unpleasant if she had not gone to a gynecologist who was specially trained in abortion care.

A study published earlier this year in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology by researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill looked at which clinicians were most likely to provide a paracervical block like lidocaine for an IUD. The authors found that 79 percent of the patients who got the local anesthetic were treated by physicians who are board-certified in complex family planning, a gynecological subspecialty that focuses on pregnancy prevention, pregnancy loss, and abortion.

In other words, if you want an IUD but are afraid of the pain, the cheat code is to call up your local abortion provider. These findings coincide with growing demand from patients for better pain management for IUDs and other in-office gynecological procedures, like endometrial biopsies and uterine aspirations.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists seemed to respond this spring by issuing updated guidelines stating pain management should be offered—even though it “may be perceived by health care professionals as unnecessary.” Also, he told clinicians to take a collaborative, patient-centered approach in deciding the direction of care.

The fact that physicians had to be told this speaks to the paternalism that often permeates medicine, Udodiri R. Okwandu, a historian at Rutgers University who specializes in Black women's experiences within reproductive medicine and psychiatry, told me. Part of the reason that complex family planning residents are more likely to provide pain management for IUD placements comes down to training. For a first-trimester abortion that involves cervical dilation and suction, applying a paracervical block is standard. It was with this procedure that Danielle Tsevat, the lead author of the Chapel Hill study, learned how to administer it, which she told me is “pretty straightforward and easy.” Because IUDs involve the same anatomy as a miscarriage or termination, the same pain management methods apply.

However, while Tsevat observed several OB-GYNs placing IUDs during her residency, she says one of the only instructors who regularly applied lidocaine specialized in complex family planning. Wells didn't realize Colleen Krajewski was board-certified in abortion and contraception care when she scheduled her IUD. But she now recommends the gynecologist to her friends, as she found Krajewski to be the “most empathetic” physician she’s ever had.

At the start of the IUD appointment, Wells recalls that Krajewski explained the entire process in detail and emphasized that she could stop the procedure at any time. Krajewski says this is her practice for all procedures, including abortions, since she wants patients to fully understand the risks and benefits, and feel in control of their health care.

Also, after every IUD insertion, Krajewski offers patients a cup of tea—a routine picked up while working for Planned Parenthood and similar clinics. “Any abortion recovery room I've ever been in has the good tea,” Krajewski told me, adding that it's usually staff who pay for these refreshments since clinics often operate on shoestring budgets.

Because applying lidocaine takes extra time, Krajweski says some gynecologists look at her sideways for using it for IUDs, as well as endometrial biopsies. This was even more the case 10 years ago, when evidence of the medication's effectiveness was less comprehensive. But Krajweski says her patients' responses prove that the medication does work, and she'd rather take a little extra time if it reduces the risk of someone leaving her office feeling violated and traumatized.

Krajweski's approach gets to Tsevat's second theory: People can feel vulnerable when seeking abortion care—some are dealing with economic instability, religious stigma, or domestic violence—and so these clinicians learn to prioritize patients' autonomy and comfort.

“Pain management is absolutely linked to reproductive autonomy, because it puts a person's needs, experiences, and values at the forefront,” Sadia Haider, president of the Society of Family Planning, told me via email. The onus not only falls on individual clinicians, argues Haider; health systems should also prioritize trauma-informed care and shared decision-making.

But as more abortion providers shutter, Okwandu warned that an “insidious consequence” might be that fewer clinics will offer pain management for IUDs. This means that more patients who want contraception to manage periods, prevent pregnancy, or reduce pain caused by conditions like endometriosis might have to undergo painful procedures to receive one—if they're able to receive one at all. Black women and people from other marginalized communities, along with rural and low-income patients, will feel an outsized impact, she said.

Wells won't have to worry about that for a while, as her IUD will last her through the next two presidential elections. Soon she won't have to deal with a monthly period either: Within a year of getting an IUD, most people stop menstruating. And not getting your period is a freedom in itself.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.